by Lauren McCormack, Executive Director, Marblehead Museum

last updated 5/25/2021

Joseph & Lucretia Brown, known in town lore as "Black Joe" and "Aunt Creese," were People of Color who lived on Gingerbread Hill from about 1790 through their deaths in 1834 and 1857, respectively. Stories of them, the tavern they owned, and the cookies (Joe Froggers) that Lucretia may have invented are many. But what is fact and what is myth? How do we know the difference?

On this page, you will find information about the real Joseph and Lucretia, as well as some sources for the stories told about them. In studying the lives of People of Color, there is often a dearth of documentary records. At times, we must rely on oral history.

PLEASE NOTE: Research is ongoing and more will be added to this site over time. Please check back occasionally.

The Early Years

Joseph Brown

Joseph Brown was born November 18, 1749 in North Kingstown, Rhode Island, the enslaved person of Beriah Brown II (1714-1792), Sheriff of Washington County, RI [NARA]. According to 19th-century historian Samuel Roads, Jr., Joseph was the son of a Gay Head (Aquinnah Wampanoag on Martha's Vineyard) Native man and a woman of African descent [Roads 1897: 288]. As an enslaved person in the Brown household, Joseph likely lived, worked, or at least spent time in Beriah's home, now owned by the Newport Restoration Foundation, which originally stood near the intersection of modern-day Route 2 and Route 102 in North Kingstown.

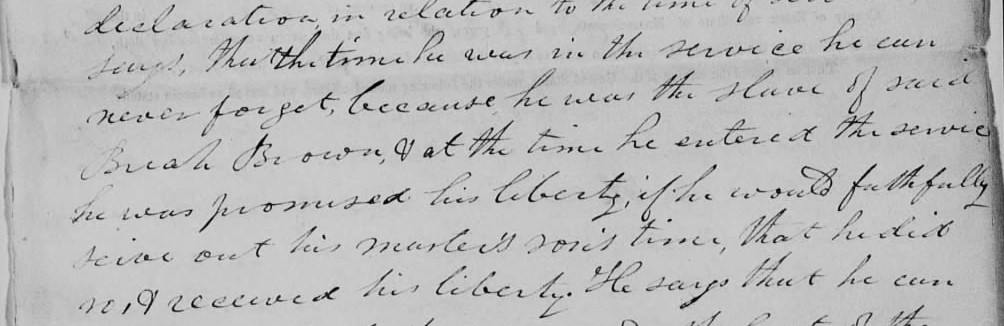

Little is yet known of Joseph's childhood or young adulthood. According to his own testimony in his Revolutionary War Pension application, filed in 1832 when he was 83 years old, Joseph enlisted around the "middle" of the War as a substitute for Beriah's son Christopher, "who left the company to go a privateering." He served ten months and twenty days to complete Christopher's enlistment, during which time Joseph served alongside about 60 other men guarding Boston Neck and then Greenwich along the Narragansett Bay [NARA]. Though Joseph does not specify his company in the pension document, it is likely that he served in the 2nd Rhode Island Regiment, based on his own identification of his commanding officers, Capt. Dyer and Lieut. Caleb Allen.

In an amendment to the pension application, Joseph adds that "the time he was in service, he can never forget" because Beriah, his "master," "promised his liberty, if he would faithfully serve out his master's son's time." Joseph goes on to declare that "he did so & received his liberty" [NARA].

Lucretia Thomas

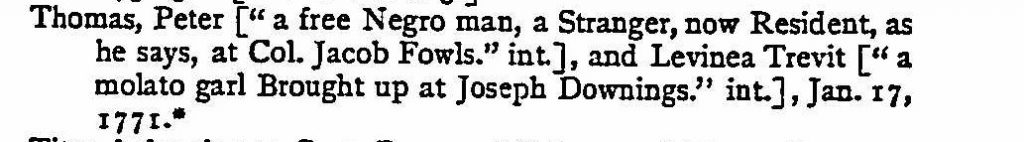

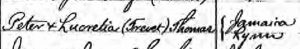

Lucretia's early years are even more opaque than Joseph's. Lucretia was born to Peter & Lucretia Thomas, probably in Salem, on September 15, 1773. According to Samuel Roads, her parents had been enslaved to Samuel Tucker in Marblehead but manumitted (freed) before or around the time of the Revolutionary War [Roads 1897: ?]. However, a newly discovered marriage record for Lucretia's parents tells a different story. In the published vital records of Lynn, Massachusetts, listed under "Negro" marriages, is this entry:

In this document, Lucretia, Senior's name is listed as Levinea. A mistake? Was Lucretia a nickname? Did she change her name after marriage? In later years, she appears in death records as Lucretia. And what is her connection to the Trevit/Trevett family? The Trevett's were a prominent Marblehead family of the time, but their connection to the Lynn Trevit's is unclear. We also do not yet know if Levinea was ever enslaved by the Trevit family.

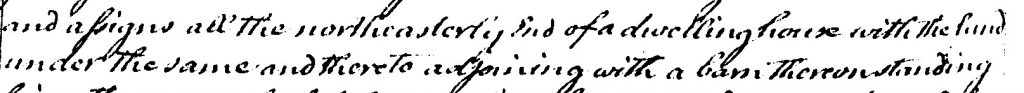

What is fascinating about this marriage document is the description of each individual. Peter Thomas was a free Black Man, a "Stranger," meaning he was not from Lynn originally but resided there by 1771 at "Col. Jacob Fowls [sic]" house. Col. Jacob Fowle, Sr., was a wealthy merchant who had property in both Marblehead and Lynn. Likely Lynn was his country seat. He conducted business alongside other well-known Marblehead merchants, such as Jeremiah Lee, Robert "King" Hooper, and Samuel White, among others. He was very active in Marblehead government as well. Fowle died in 1771, and his son, Jacob Fowle, Jr., took over his business interests. Peter Thomas was a free man but perhaps he worked for Fowle? Did Fowle's death leave Joseph free to marry and move to Salem?

Peter and Levinea/Lucretia Thomas give birth to Lucretia in 1773. She may have been their first born. They have at least five other children, all daughters and all born in Salem. None of them appear in the published vital records, but we do have death records and other mentions of them from which can identify them as Peter and Lucretia's children: Venus, born circa 1779; Hannah, born circa 1782; and Mercy, born circa 1786; Lucy; and Patience.

Hannah and Mercy's death records also reveal a key piece of information about their parents. In both documents, 1861 and 1871, respectively, Peter and Lucretia Thomas are identified as their parents. Lucretia, Sr., was born in Lynn, and Peter was born in Jamaica!

The Couple, Joseph and Lucretia

The documentary record of Joseph's story pauses from the time he left the army until April 22, 1788, when he surfaces in Marblehead on "A List of Negros residing in this town [MHC]." This may be the list that provoked the Town's Selectmen to "warn the Affricans [sic] and Negroes residing in this Town, to depart." On the list, Joseph is marked as a Rhode Island native and a curious "X" by his name denotes that he "lives & cohabits with [a] white women" [MHC]. Could Joseph have been a boarder in a household of a white woman? Was he in a relationship with a white woman? We do not know.

Just how Joseph ended up in Marblehead from Rhode Island is a mystery. However, in his pension application amendment, Joseph writes that there was no one left in 1832 to attest to his service in the War, "the last man he knew of who served with him died in Marblehead two or three years ago" [NARA]. Had he served alongside Marblehead men during the War and sought them out after gaining his freedom? Or had multiple Rhode Island veterans made their way to Marblehead, perhaps after obtaining their liberty? Further research is required to try to answer these questions.

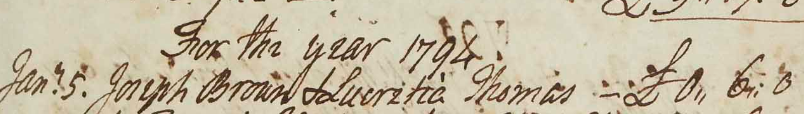

On October 15, 1793, Joseph's name appears on a deed establishing him as a mortgagee to Mary Seward for the "northeasterly end of a dwelling house with the land under the same and thereto adjoining with a barn thereon standing" [SEDRD 156:275]. Joseph, who is identified as a laborer, is now a property owner, relatively rare among People of Color in the Early Republic.

Were Joseph and Lucretia already courting when Joseph purchased the property? Was this to be their home together? We do not know for sure, but on January 5, 1794, Joseph Brown married Lucretia Thomas at the 2nd Congregational Church on Mugford Street. In her pension petition decades later, Lucretia identifies the Rev. Isaac Story as the officiant of the ceremony.

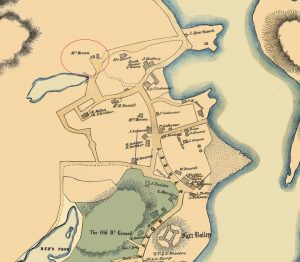

Now married, the two took up residence on Gingerbread Hill, in the half of the house Joseph purchased two months before. In 1796, Joseph purchased the other half of the house from William Peach of Newbury [SEDRD 163:49]. Soon, they open a tavern. From this point, the mythology of "Black Joe" and "Aunt Creese" arose.

Tavernkeepers on Gingerbread Hill and the Mythologizing of "Black Joe" and "Aunt Creese"

Joseph and Lucretia's tavern does not appear in newspapers. There are no directories from the period still extant that might list them. Perhaps hidden somewhere in the town records is a tavern or innholder's license in one or both of their names. But in people's reminiscences of the couple, the tavern played a significant role.

In newspaper articles throughout the latter half of the 19th century and even into the early 20th century, longtime residents included the Browns in their memories of important people and events in town. Most often they are associated with Election, or 'Lection," Week, the last week in May. Stories differ slightly, but the week was a holiday for the whole town. People were off work and children off from school. The real purpose of the holiday was to honor the General Court’s election in Boston, but locally it was also a time for the militia to turn out to drill and elect officers. The center of activity, “the place par excellence in which to keep ‘lection,” was the Brown’s tavern [Marblehead Messenger, July 16, 1937, 5]. The week was one of frivolity and celebration. Most stories of Election Week resemble Joseph S. Robinson’s recollections: the Browns "provided at their home on Gingerbread Hill a continuous round of fun and frolic. 'Lecshun buns and cakes added to the enjoyment... the grounds [around the tavern] were filled with men pitching coppers [pennies], or trying their luck at the wheel of fortune, while [Lucretia] dispensed refreshments to the thirsty" [Marblehead Messenger, April 12, 1929, 10]. At night, the activities moved inside where Joseph played the fiddle while townspeople danced jigs and reels all night long. A common refrain in some of the stories is that Joseph only knew one tune, "Yankee Doodle," but played it in different tempos to keep the dancers satisfied.

Some of these descriptions describe drunken revelry at the tavern, but most depict scenes of recreation and enjoyment by young and old, male and female. Lucretia's cooking (buns and cakes) and Joseph's fiddle-playing are always the highlights.

It is during the retelling of these memories that the elders, almost to a man (and they were almost all men), refer to Joseph and Lucretia by their nicknames, "Black Joe" and "Aunt Creese." Some insist that Joseph and Lucretia were only known by these monikers [e.g., "no one ever called him anything but Black Joe." Marblehead Messenger, January 29, 1937, 3]. We may never know if they were called those names to their faces, but it is likely. The names hint at the racist stereotypes and tropes that existed throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, most often depicted in cartoons, minstrelsy, and other less-than-flattering representations of people of African descent. Only one un-named author repeatedly refers to Joseph as "Mr. Brown" and "Mr. Joseph Brown" [Marblehead Messenger, May 28, 1886. 2].

At the same time and in the same articles, the authors reveal feelings of warmth and affection toward the couple, sometimes even awe, raising them to an almost mythical status. Joseph is depicted like a king on his throne, presiding over the festivities with his fiddle and bow. Lucretia fulfilled their culinary dreams, dispensing much sought after treats and refreshments from the temporary counter in her kitchen [Marblehead Messenger, January 18, 1901, 4]. In the juvenile memories of one writer, Joseph and Lucretia were legends:

In the center of the room, in a large armchair was seated a large, burly specimen of the African race. I eyed him curiously. I had never seen before such a large specimen of humanity; he evidently was six feet in height and though appearing very old, his countenance beamed with mirth [Marblehead Messenger, May 28, 1886, 2].

No images of the Browns exist (Joseph died before the advent of photography). In their lifetimes, portraits, photographs, and even silhouettes were an extra expense many could not justify. Instead, we are reliant on memories such as the one above for the only hints we have as to the couple's physical characteristics. It was oft-repeated that Joseph was a tall and large man. The same author quoted above remembered, "After I worked at my trade of shoemaking some time, Mr. Brown came to the shop to have a pair of shoes made; and we found it necessary to reconstruct a large, full, No. 12 fishing-boot last by additions of leather, making it considerably longer and wider." Others commented on how Joseph kept time with his fiddle by beating his large feet [ibid.].

These chroniclers were youngsters when they knew Joseph and Lucretia. Sometimes their memories reflect this. In 1931, Joseph S. Wormstead, recounting his stories at age 93, was “one of the few persons…who can recall this famous old couple” [Marblehead Messenger, September 18, 1931, 2]. He remembered the couple as “lovable” [ibid.]. In fact, Wormstead was born four years after Joseph's death so his memories, however accurate they may have been, could only have been of Lucretia. Everything he knew about Joseph was learned from others.

In a fictionalized story based on one woman’s neighbors in Marblehead, she recalled visiting the tavern as a child with her friend to purchase rose water from Lucretia:

As a child, she saw Joseph's skin color as worthy of comment. Perhaps he represented an "other-ness" that was unfamiliar to her, though other People of Color did reside in Marblehead in the early 19th century.

As for Lucretia, she is described as a “jovial lady,” who kept busy day and night during Election Week “dispensing free beer and cakes to the visitors” [Marblehead Messenger, January 29, 1937, 3]. Though gambling took place at the tavern, one writer is quick to point out that Lucretia received no monetary benefit from the gaming (she took no cut), “her only concern was for the enjoyment of her guests” [ibid.] The famous Seed King of Marblehead, J.J.H. Gregory, who was born in 1827, distinctly remembered Lucretia as a “tall, dignified colored woman” [Marblehead Messenger, January 18, 1901, 4].

Indeed, it was Lucretia’s warmth and generosity that most ingrained itself in the collective memory of the town. Samuel Roads, Jr., in his History and Traditions of Marblehead, devoted a page of his book to her, describing her as a “good old soul” and remembering her as the “friend and companion alike of young and old” [1897 edition, 289]. In 1937, a newspaper writer described her as “one of the most kindly and charitable souls in the town… Her tales, which she spun while young folk congregated during the winter nights, were things of beauty. [Marblehead Messenger January 29, 1937, 3].

Both Joseph and Lucretia left a lasting legacy in Marblehead. For decades, residents recalled their warmth and generosity of spirit, the joyous celebrations they hosted yearly in May, and the central role they played in town, for young and old alike. As one anonymous author concluded in a 1937 article,

Thus comes down to us the tale of two beloved characters whose deeds and lives were simple, but of such grand simplicity that they have found a solid place in the tradition of the town of Marblehead, and as long as memories are able to pass their stores [sic] from one generation to another, the names and feats of Black Joe and Aunt Crese of Gingerbread Hill will live [Marblehead Messenger, January 29, 1937, 3].

Joseph's Pension, Death, and Lucretia's Pension Claim

A Veteran's Pension

On June 7, 1832, Congress passed an Act broadly extending pension benefits to those who served in the Revolutionary War. On October 3rd of that year, Joseph, at the age of 83, appeared before a judge at the Essex County Probate Court to declare his service in order to receive his pension. Joseph recounted how he enlisted as a substitute for his master's son, where he served, under whom, and for how long. As witnesses to his character and the veracity of his claims, he brought with him to court Rev. Samuel Dana of the 1st Congregational Church (Old North) of Marblehead and the local Magistrate, Nathan Bowen. These two persons of import signed their names to Joseph's deposition attesting to his honestly and his war record [NARA].

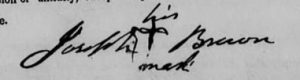

At the end of his declaration, likely written out for him by another, Joseph, in the shaky hand of old age, scratched an "X." This, "his mark," substituted for his signature. He had made the same X on the 1793 property deed. Joseph, the successful tavernkeeper, was illiterate.

Despite lacking written proof of his service, such as enlistment or discharge papers, the Federal Government award Joseph a pension of $35.53 per year, retroactive to March 4, 1831.

Joseph's Death

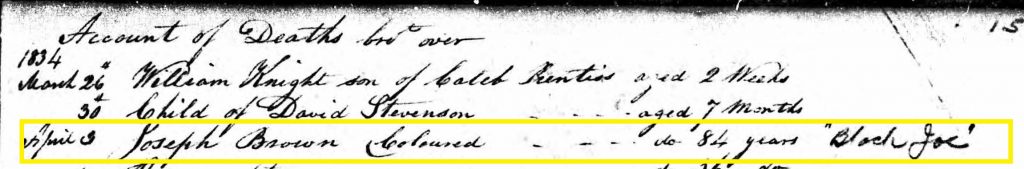

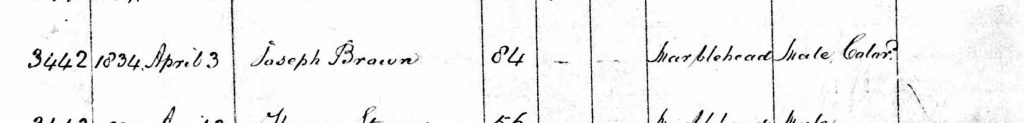

Joseph died of an unspecified illness on April 3, 1834. His passing is listed in two separate town ledger books:

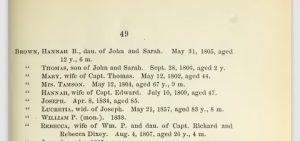

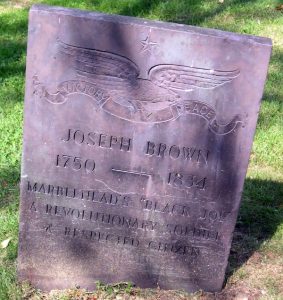

Joseph was buried at Old Burial Hill. His grave was marked by what was likely a simple stone which read, "Joseph Brown April 8, 1834, Aged 85" [Derby: 49].

Joseph died intestate, meaning without a will. This likely made the probate process long and arduous, while creditors were paid, debts called in, and the estate settled. In order to inherit the property, Lucretia had to petition the Massachusetts House of Representatives. A notice of her petition appears eight months after Joseph's death in the January 23, 1835 issue of the Lowell Patriot:

As Joseph's wife, Lucretia was his lawful heir. The couple had no biological children, but they did have an adopted daughter, Lucy, the granddaughter of Lucretia's late sister.

Lucretia Seeks Joseph's Pension

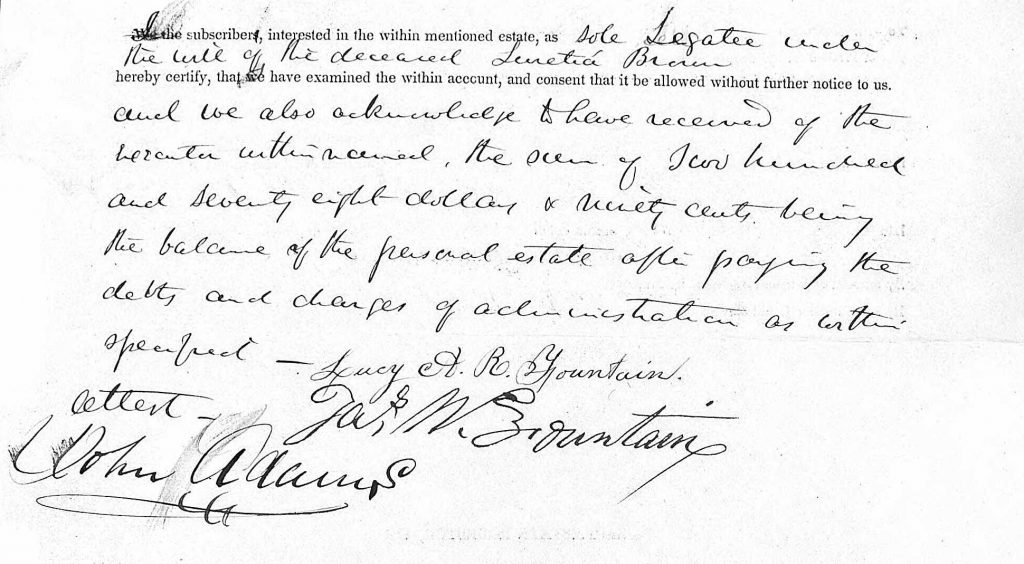

According to various Acts of Congress, Lucretia, upon Joseph's death, was entitled to his pension (1848) and the Bounty Land he qualified for (1855). Lucretia's great-niece and adopted daughter, Lucy, along with Lucy's husband James W. Fountaine, helped Lucretia apply for the remainder of her husband's pension from his Revolutionary War service.

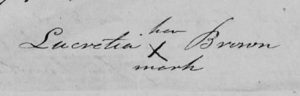

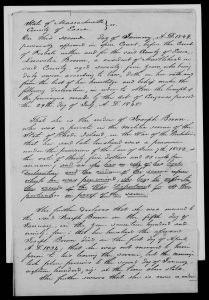

On January 2, 1849, a 75-year-old Lucretia stepped before the Essex County Probate Court judge to make her case for receiving Joseph's pension under a newly passed Act of Congress allowing widows of pensioned Revolutionary War veterans to receive the money. She attested to their marriage, even providing sworn and signed affidavits from the present pastor of Marblehead's 2nd Congregational Church to prove the deed. She also reminded the court that Joseph received his pension using War Department records, having retained or received no enlistment or discharge papers. She closed by swearing to the fact that she had not remarried since Joseph's decease, and then placed her "mark" on the document. She, like Joseph, was illiterate.

Lucretia's petition was successful, and she was pensioned at the same rate as Joseph [NARA].

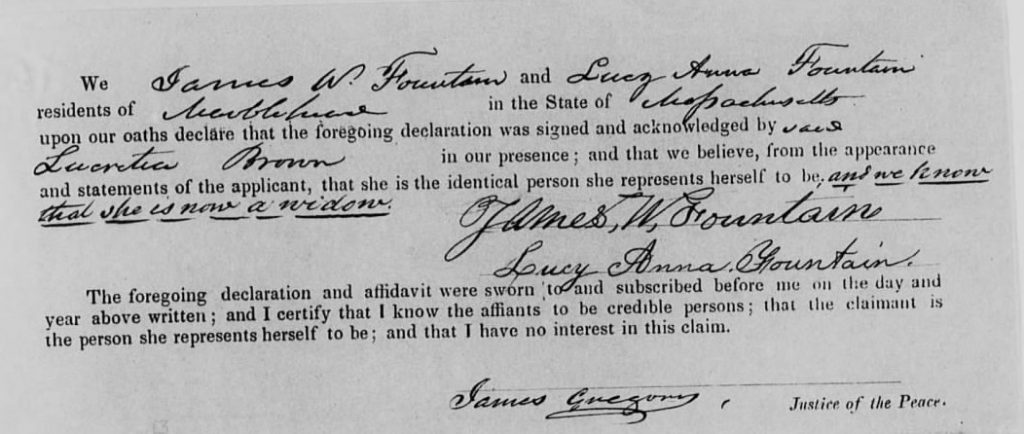

Six years later, we find Lucretia, now 81 years old, again seeking recompense from the government for Joseph's service. She applies as a widow for a Bounty Land Warrant, land given to pensioners for their service from unsettled, Federally-owned lands in Ohio, Pennsylvania, New York, and other states and territories. In her petition, Lucretia swears in her affidavit, again written for her by someone else, that she never remarried after Joseph's death and that they had both received a government pension for his service. Her adopted daughter and son-in-law testify to the accuracy of her claims, as well as the veracity of her identity:

A short notice appears in the February 28, 1856 edition of the Daily Globe referring to a petition in the U.S. House of Representatives to consider Lucretia's Bounty Land Warrant application:

At this time, we have no evidence that Lucretia was granted land.

Lucretia: A Female Entrepreneur

Though today Joseph is the better known of the couple ("Black Joe's Tavern," "Black Joe's Pond"), it is Lucretia who stands out in the early records for her business acumen and enterprising nature. In most stories about Lucretia published in the late 19th and early 20th centuries by those who actually knew the couple, Lucretia was the one selling the beer, "which she brewed from her own formula;" she was cooking the wedding cakes, election buns, and 'lassy cakes; and she was picking roses and turning them into profitable rose water.

Joseph Wormstead remembered her as an "industrious woman" and "very smart." During rose season, Lucretia could be found in the fields and pastures, especially by the old grave yards, early in the mornings collecting massive quantities of dew-covered rose petals. These she brought home, salted, and stored in firkins. At the end of the season, all the gathered and salted petals were put in a large iron kettle, the top sealed tightly with clay, and boiled. Vapor came out of the kettle, through a tube inside a barrel of cold water. The cold water condensed the vapor into liquid droplets Lucretia collected and bottled. It was said that during this process, "the air for half a mile was permeated with the odor of the roses" [J.S. Robinson, "'Aunt Creese' Found Graveyards Source of Income, Marblehead Messenger, November 25, 1929, 1]. Rose water was an extremely popular cooking additive in the mid 19th century, as well as a perfume used by many to cover up unwanted scents. Lucretia "was expert in the process of extracting the precious scent" and readily sold hers for 50 cents a bottle, about equal to half a day's labor for an unskilled farmhand ["Grand Army Veteran, 93, Recalls Events of Early Days," Marblehead Messenger, September 18, 1931, 2].

If Lucretia was popular for her rose water, her cakes made her a star. Though we do not know what flavors she was known for nor do we know anything about her techniques, we do know she was sought after for her baking skills. As Samuel Roads wrote, "whose presence was more indispensable at the marriage feast than that of this old colored woman, the delicious flavor of whose wedding cake made her famous for miles around" [1897 edition, 289]. "It was the custom," one man remembered, "when ordering a wedding cake, to have Aunt Crese bake it, for its delicious flavor made her famous for miles around" [Marblehead Messenger, January 29, 1937, 3].

And, of course, we can not forget Joe Froggers. These gingerbread and molasses cookies are a staple in Marblehead to this day. According to legend, these shelf-stable cookies, brought on long sea voyages, were invented by Lucretia and named after Joseph and for their resemblance to the lily pads in the frog pond near the Brown's tavern. That said, forms of gingerbread cakes and cookies date back to the earliest published cookbook in America, Amelia Simmons' 1796 American Cookery, and even farther back into colonial times. Did Lucretia alter the recipe somehow, perhaps removing butter or milk to keep the cookie fresher longer?

In the earliest reminiscences of Joseph and Lucretia, mostly centered around Election Day, Joe Froggers are not mentioned by name. One writer remembered "'lassy cake," a gingerbread confection Lucretia gave to her hungry taverngoers [J.S. Robinson, "'Aunt Creese' Found Graveyards Source of Income, Marblehead Messenger, November 25, 1929, 6]. She is generally known for her cakes in these stories, but not always gingerbread cakes. Others claim that Gingerbread Hill is named for her "lassy cakes." Could the myth of Joe Froggers have evolved over time, after the passing of Joseph and Lucretia? We may never know. Nevertheless, they have made such a mark on African American culinary history that Joe Froggers are served in the café of the National Museum of African American History in Washington, D.C.

It is poignant that Joseph and Lucretia are best known for their connection to Joe Froggers, a cookie reliant on molasses and sugar, among other things. Those two ingredients directly related to the slave trade and the trade in goods produced by enslaved people. Joseph and Lucretia were just making a living, but the irony that their fame came from a product so closely related to the subjugation of their race should not be lost in the perpetuation of the story.

Lucretia's Death

Lucretia outlived her husband by 23 years. She never remarried, raising her great-niece and adopted granddaughter, Lucy Ann, as a single mother. She remained in the house on Gingerbread Hill. By the 1850 Federal Census, Lucy had married James W. Fountaine and moved out to start her own household at 20 Stacey Street. Lucretia, now 75 years old, rented part of her home to Robert Cary, a White farmer from England, his wife, and six children, ranging in age from 2 to 15 years old. What a hectic house that must have been!

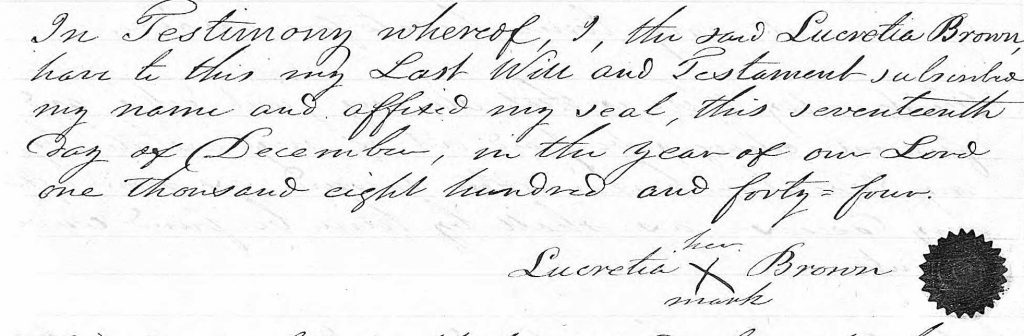

In her final days, if not for some time before that, Lucretia lived with Lucy and James. Interestingly, in Lucretia's will, dated 1844, Lucretia lists herself as a widow "of Salem" [Essex County Probate Records, NEHGS, 33754]. Did Lucretia move back and forth between Salem and Marblehead, between various family members, as her health allowed? No matter where she lived, her ties to Marblehead remained strong. Three of Marblehead's most prominent citizens witnessed (and one likely transcribed) her Last Will and Testament, James Gregory, Sr., Ruth Gregory, and J.J.H. Gregory [ibid.].

Lucretia may have been in ill health for some time, forcing her to face her own mortality and prepare her estate for her inevitable demise. Her will is short and concise. She leaves all her goods, after debts and funeral expenses are paid, to Lucy Ann Reed Brown, her adopted daughter and granddaughter of Lucretia's late sister Lucy Cooper. Lucretia then acknowledges her remaining siblings, Venus Chew, Hannah Williams, Patience Jointer, and Mercy Morris. She "leave[s] them all my best wishes, but I do not feel that I can make any provision for them." Lucretia goes on to nominate her "friend," Thomas Boardman, a fellow Marblehead baker, to be the executor of her estate. With her business complete, Lucretia makes her mark, officially approving the document [ibid.].

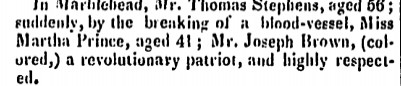

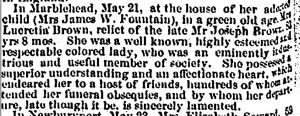

On May 21, 1857, in the home of Lucy and James W. Fountaine, at 20 Stacey Street, Lucretia died of old age. Her death did not pass unnoticed. An obituary appeared in the local papers. It shows, without a doubt, the impact and legacy Lucretia left on this small town:

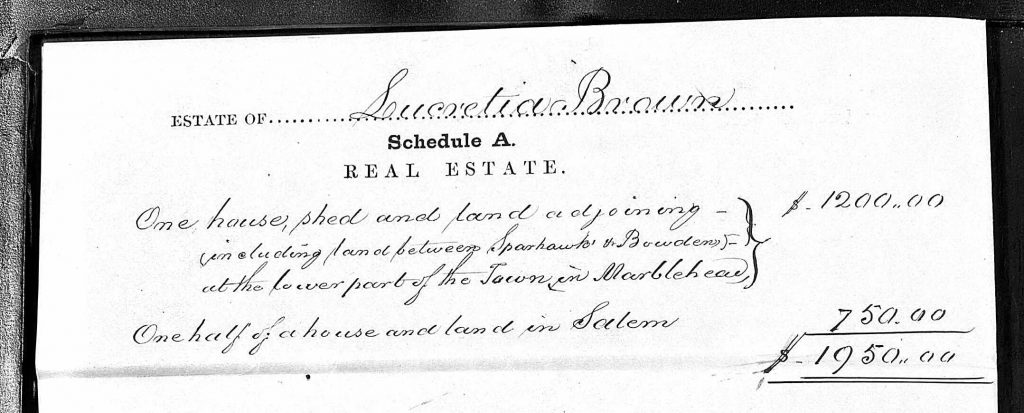

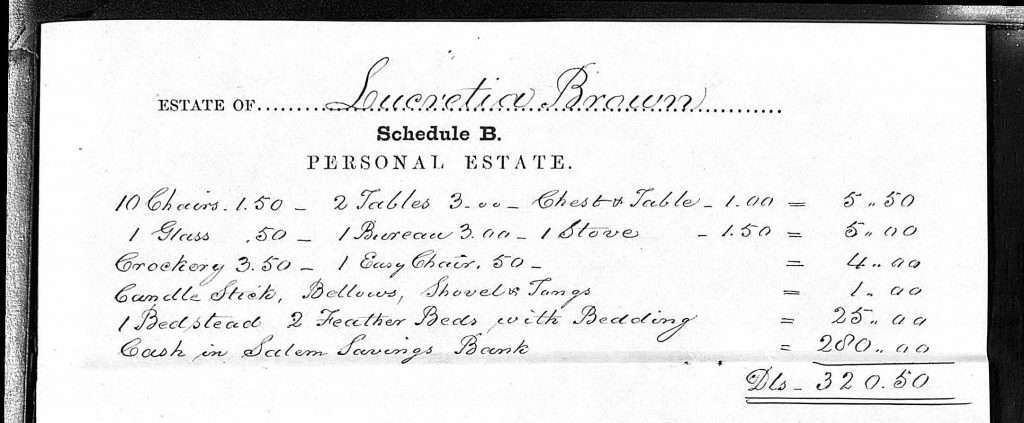

Thomas Boardman, the executor of Lucretia's estate, was charged with collecting any outstanding debts. He did so by placing an announcement in the Salem Gazette and posting the same at the corner of State and Front Streets in Marblehead. He also oversaw the inventory of Lucretia's real estate and worldly goods.

Despite owning two properties, the house on Gingerbread Hill and another part of a building in Salem, Lucretia had very little in the way of personal property.

The residue of the estate was delivered to Lucy in October 1857.

Where are They Buried? The Mystery Remains

According to 19th-century town historians, J.J.H. Gregory and Samuel Roads, Jr., there was a place in town know as the "Negro Burying Ground" near the intersection of Back (now Elm) Street and Pearl Street. However, the earthly remains of Joseph and Lucretia were not relegated to that spot. Instead, it is currently believed they were buried in Old Burial Hill, down the back side of the hill near the spot of their present marker (by the Glover tomb).

In 1874, Perley Derby transcribed portions of markers at Old Burial Hill. Joseph and Lucretia both appear on his list:

From these entries, we know that one or two stones existed for the couple, and here we have at least part of the inscription(s) on the stone(s). We know, however, from other extant stones that Derby did not always transcribe stones in their entirety, so we do not know if more information existed on the stones than he has recorded.

The stone or stones Derby transcribed in 1874 had disappeared by the 1930s. In 1932, the Marblehead Historical Society, now the Marblehead Museum, marked Joseph's grave with a new marker [Marblehead Messenger, May 20, 1932, 5]. Lifelong resident Standley Goodwin, who grew up near the cemetery, remembers this marker. It, too, had disappeared by the 1970s. In the years leading up to the nation's Bicentennial, Virginia Gamage worked to install a new stone memorializing Joseph. It still exists today. Unfortunately, Lucretia seems to have disappeared in all this. No stone marks her gravesite in Old Burial Hill.

Meanwhile, in 1859, Waterside Cemetery was consecrated in Marblehead. In 1865, James W. Fountaine and Lucy A. R. Fountaine, Lucretia's great niece and adopted daughter, purchased a plot after their son passed away at the age of 16 [according to email sent to author from Catherine M. Kobialka, Superintendent, Marblehead Cemetery Department, 1/25/2021]. At some point, the Fountaines erected this stone to Lucretia and Joseph:

Was this the couple's stone at Old Burial Hill which the Fountaines removed to Waterside to reside with the rest of family? If that is the case, why is Joseph's name on the bottom even though he died first? Instead, was this a different stone commissioned by the Fountaines? The last, and most outrageous, theory is the the Fountaines had Joseph and Lucretia exhumed and reburied in Waterside Cemetery. The Cemetery Department's records are spotty and do not help answer these lingering questions.

"Black Heritage in Marblehead: Joseph & Lucretia Brown," a short film by the Marblehead Racial Justice Team

Released February 2021

The Inclusive History Project is produced by the Marblehead Racial Justice Team, a community organization of Marblehead, Massachusetts dedicated to fighting racism in all its forms.

Sources

SERD. Southern Essex Registry of Deeds. Salemdeeds.com

MVR. Marblehead Vital Records to 1850. Ma-vitalrecords.org. Also published.

MM. Marblehead Museum Collection

Ancestry.com. Massachusetts, U.S., Town and Vital Records, 1620-1988 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2011. Original data: Town and City Clerks of Massachusetts. Massachusetts Vital and Town Records. Provo, UT: Holbrook Research Institute (Jay and Delene Holbrook).

“Aunt ‘Crease and Ma’am Sociable Had Lively Times” Marblehead Messenger, January 10, 1930. 7.

Catherine M. Kobialka, Superintendent, Marblehead Cemetery Department, email correspondence with author, 1/25/2021.

Death Notice, Columbian Centinel, April 9, 1834

"Grand Army Veteran, 93, Recalls Events of Early Days," Marblehead Messenger, September 18, 1931, 2.

Marblehead Historical Commission (MHC). “Negroes List of 1754-1788.” 2009-100-1Os5.17.

J.J.H. Gregory. Marblehead Messenger, January 18, 1901. 4.

Joseph Brown (Lucretia Brown) Revolutionary War Pensions. Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty-Land Warrant Application Files. The National Archives & Records Administration (NARA). M804. 300022. RG 15. Roll 0372.

J.S. Robinson, "'Aunt Creese' Found Graveyards Source of Income, Marblehead Messenger, November 25, 1929, 1

“Life in Marblehead.” Marblehead Messenger, March 11, 1921. 1, 8.

The Lowell Patriot. January 23, 1835.

Marblehead Messenger, May 20, 1932, 5.

Marblehead Messenger, July 16, 1937. 5.

Marblehead Messenger, April 12, 1929. 10.

Marblehead Messenger, January 29, 1937. 3.

“More Reminiscences of School Days.” Marblehead Messenger, May 28, 1886, 2.

Samuel Roads, Jr. The History and Traditions of Marblehead. Marblehead: N. Allen Lindsey & Co., 1897.

Susan G. Knight's Pete, the Cunner Boy Or, the Boy Who Kept the Fifth Commandment, published by Henry Hoyt in Boston, 1862, 82.

Perley Derby's "Inscriptions from the Burial Grounds of Marblehead, Mass." Historical Collections of the Essex Institute, Vol. XII; No. 1, 1874: 49.

SERD, 33754 1857 Lucretia Brown